![]()

Issue Date: April 15, 2000

T H E I N T E R N E T W O R L D C O V E R S T O R Y

The Truth About Patents

Five Reasons They'll Have Limited Impact On The Web's Evolution

Stories by Bill Roberts

Photos by Richard Morganstein

The Truth About Patents

Reason 1: Lawsuits Are Too Expensive

Reason 2: They'd Rather License Than Fight

Reason 3: Market Forces Rule

Reason 4: Busted in Court

Reason 5: Time Is an Ally

When a Patent Makes Sense

Vulnerable Patents

The patent frenzy sweeping the Internet doesn't phase Jerry Kaplan, CEO of Egghead.com. "Patents will not determine the near-term success or failure of any Internet company," he says. Kaplan's own strategy: He's secured a patent for the company's online auction method and hopes to license the technology to others - but at this point he has no plans to sue anyone.

Notwithstanding Kaplan's advice - and the fact that there are many Internet CEOs who agree with him - it's sure tough not to get panicked about patents.

Two widely watched lawsuits alleging patent infringement do nothing to soothe most fears. In one case, Amazon.com is battling to block Barnesandnoble.com from using Amazon's "1-Click" Web shopping feature. In another case, Priceline.com claims Microsoft is improperly using Priceline's reverse-auction technology.

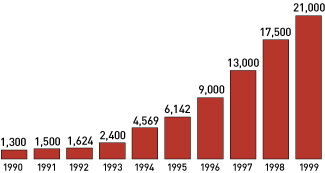

Internet companies, many flush with resources from venture capitalists or successful IPOs, are aggressively getting patent applications into the pipeline. A few hundred Internet-related patents have been granted, and hundreds, if not thousands, more may be wending their way through the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). Many insiders are wondering: Is this the point in Internet history when powerhouses begin to use patents to put a stranglehold on e-commerce?

Not likely. Patents are important, and every company needs a strategy to protect its intellectual property. But any fear of an impending patent war that would forever change the shape of the Internet or e-commerce is overwrought. "They're a small-to-moderate competitive tool people use to threaten others," Kaplan says. It's rare that any single patent gives the holder a lock on a technology or a business method.

Even Amazon.com's CEO, Jeff Bezos, admits there's much more to building a successful Internet business than lots of patents. "The vast majority of our competitive advantage will continue to come not from patents, but from raising the bar on things like service, price, and selection," he wrote to customers in a recent open message. In that letter, written after he was harshly criticized for his company's patent strategy, Bezos joined the chorus of people calling for reform of the patent approval process. He recommends the lifespan be shortened to 5 years or less, instead of 17, for patents that cover business methods and software - the predominant type of Internet patents.

Some patents now being issued are for the nuts and bolts of the technology itself - what patents have traditionally protected. Many, though, are a relatively new breed of patent issued to protect business methods that have been migrated from the physical world to the Internet - Priceline's reverse-auction format, for example. Several infringement suits have been filed, at least one of which has been settled out of court for $15 million. And several companies are offering patent licenses, for a fee.

Paul Esdale, vice president of corporate development at Open Market Inc., is among the executives pursuing an aggressive patent strategy. "Those who believe that Internet patents aren't relevant are just kidding themselves," says Esdale, who is trying to license technology for five patents involving e-commerce software.

But will patents dictate how the Internet evolves? Probably not, says Ullas Niak, an investment analyst at First Albany Corp. who evaluates Internet companies. Niak rates patents much lower in importance than a company's potential market, management, and other factors. "Patents serve mainly as a deterrent to competitors," he says.

Patents will have the same impact on the Internet as they've had elsewhere. They'll force competitors to pay attention to each other's innovations, explore licensing and cross-licensing options, and sue when necessary. They'll spur innovation and protect inventors, which are the same goals the patent system had when it was founded by Ben Franklin in the early days of the Republic.

With one difference: Because the speed of Internet innovation is so much faster than the pace at which patents are granted, licenses negotiated, and suits fought, many patents may quickly prove irrelevant. Patents take three years or longer to be granted, licenses can take a year or longer to negotiate, and infringement suits take years to plod through trial and appeals. Internet innovation, however, is measured in weeks or months. With this in mind, experts identify five reasons why Internet patents, although important, will only have a modest impact on the evolution of the Web and e-commerce.

Next: Reason 1: Lawsuits Are Too Expensive

Copyright ©

2000 by Internet World Media, A Penton Media, Inc.

Company.